I’m currently working on a Drupal project, and it did well to remind me as to why I’ve switched most of my development over to Django some time ago. I have a comprehensive comparison in the works between these two frameworks and a few others as well, but for now I’d like to focus on just one thing and what it means for development in Drupal and Django: coder happiness.

Configuration over coding

Most people who have a career in software development actually, surprisingly, really like coding a lot . We code after work, perhaps hacking together a widget for personal use or contributing to an open-source project. A lot of coders write about coding as well.

One of the more frustrating things about Drupal is that most of your time spent hacking together a project does not go towards actually coding, but is spent configuring and tweaking settings in a graphical user interface. Another big lump of your time will go towards searching through the gargantuan directory listing of Drupal modules that now contains about 5.000 of those, to see if any of these modules do something you need. And the coding that does happen is split 50/50 between actually writing code yourself and getting familiar with the code of the existing modules that you’ve just installed, because you’re not happy with how this or that works and need to patch things up.

There are tremendous benefits to the reuse of existing software. The Not Invented Here syndrome is an ailment that has crippled many a good developer. It led Steve Yelvington to coin the First Rule of Coding for Drupal, namely: “We do not write code for Drupal.” Any code you or someone else on your team writes has to be documented and maintained, and can break in unexpected ways. Coding things yourself has subtle hidden costs. So Steve raises a valid point and it’s an issue that I hope to write about in the foreseeable future. But this post is about coder happiness. And, being a coder, having my work reduced to that of an administrative clerk, searching for and configuring modules, just sucks.

Yelvington is in the news biz, and he talks about how building news websites in Drupal actually goes about:

configuring and tailoring the platform to the needs of a news site is a huge creative challenge that involves fairly little in the way of heavy technology (i.e., developing new modules) but a lot of what I regard as “configuration” work, including interface design and theming.

The description of the work is accurate. But I disagree with his evaluation. There’s nothing creative about configuring a Drupal site at all. It offers very little satisfaction. It requires a lot of experience but hardly any skill.

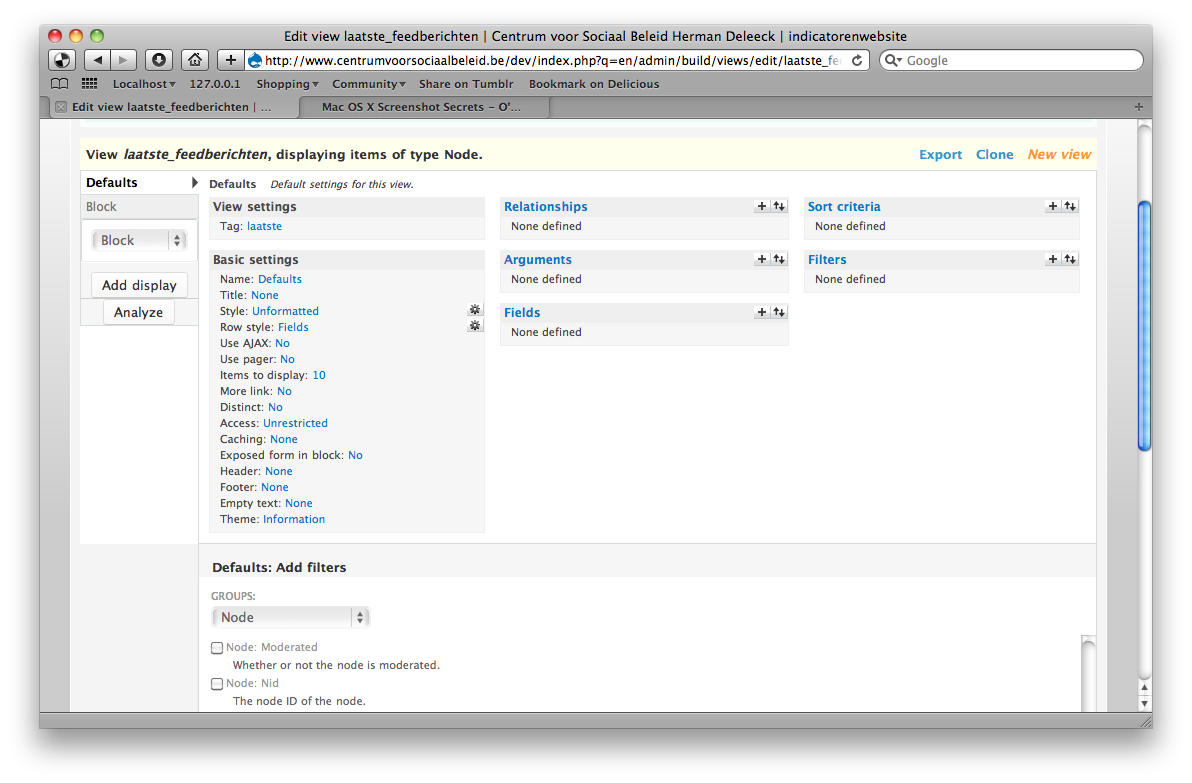

Take, for example, how you access your database in Drupal. You use the Views module. It’s incredibly flexible. It also means that instead of writing a simple line of Django ORM code like

and processing that in your view with

you get to fill out a gigantic form that generates your view, after which you’ll have to fill out a similarly large form in the Panels module to get that list displayed where you want it to. And if want to customize the html that Views produces (because, being geared towards end-users, Views is both a query builder and an html generator) you’ll have to override a bunch of theme files as well.

Easier for them is harder for me

Configuration over coding sucks. I’ll take Django’s approach any day. It doesn’t work for non-technical users, true enough. You can expect a non-technical user to complete a form but you can’t expect him or her to handle an object-relational mapper. However, I’m not a non-technical user and I don’t want to be treated like one. Easier for them is harder for me. Dries Buytaert, the project lead for Drupal, is adamant about lowering the barriers to participation on the web for non-techies. That’s really cool. But I can write code perfectly well, thank you, so that’s just not a selling point for me.

The developers behind Drupal understand that user experience (UX) and developer experience (DX) are two different things and that they can work against each other. But because they have to serve both communities, they have to compromise. Django is geared towards developers and developers only, so it can skip all these delicate discussions about how to balance the needs of developers and those of end-users and just do whatever makes the framework more productive or comfortable for coders. And it shows.

The Sharpened Knife

Clicking in menus isn’t a very satisfying way to spend your day, but that’s not the only reason why I dislike it. Coding-by-configuring takes you away from the skills that make you so valuable as a coder. You’re not advancing as a developer because you’re not learning any skills that remain valuable outside of the CMS.

I often felt that I was coding in Drupal, not in PHP. Drupal has modules and wrappers for just about anything. You can’t fault Drupal for providing so many conveniences, but it does mean that you never come into contact with e.g. the plain Google Maps API, which means that you can’t transfer that experience to other languages or frameworks.

After working with Drupal for more than three years, I started to feel that I was handicapping myself.

In Django, you’re mostly writing plain Python and using general Python libraries. Django does a lot of work for you, but it’s nonetheless fairly compact. The four-part introductory tutorial teaches about half there is to coding in Django, and can be completed in a few hours. That gives me a warm and fuzzy feeling. If I ever feel the inclination to try out, say, Ruby on Rails or Symfony, I know I have the basics down of MVC-style frameworks and can re-use my knowledge of external API‘s, so I shouldn’t find it hard to adapt.

It goes deeper than just skills. The Python and Django communities talk about programming techniques, about continuous integration, about agile methodology. Contrast that with Newspapers on Drupal, a group where I used to spend a lot of time, where almost no best practices are being shared or discussions being held about the future of online news, but rather is filled with questions about what modules to use for this or that.

Building rather than modifying

Because Drupal is still at heart a CMS (although it’s closer to a framework than most other CMSes), it’s all-encompassing. In Django you build things, which is easy. In Drupal you modify how the existing code works, so you need a good working knowledge of what can be modified and how to modify it. There are hooks, theme layer overrides, helper functions, existing modules that you can leverage and so on. Getting familiar with Drupal is not easy.

Coding in Drupal, using hooks, feels somewhat similar to aspect-oriented programming, and the same benefits and caveats apply.

If you haven’t tried out aspect-oriented programming techniques before, you should. It’s very doable in Python with some metaprogramming, and it’s a fun exercise. If you have, you know that it’s wonderfully flexible and that you can modify the behavior of your code in any way that you could possibly want. Kudos to the Drupal devs for pulling that off in a crummy language like PHP.

The trouble, though: if you’re not careful with aspect-oriented coding, the flow of code becomes unbearably opaque. While it does not often come to that point in Drupal, it does make for code that is tougher to write and maintain than it would be if you could simply change how Drupal behaves e.g. by subclassing, as you would in Django.

Regardless of which is more productive, the ‘construction’ approach just feels better to me. It’s not that big of an issue when what you need is close to what Drupal provides out of the box or through modules, but the more custom development you have to do, the more cumbersome tweaking existing behavior becomes, and the more it starts to feel like you’re working around Drupal rather than with Drupal.

Frameworks should enable you to get to the cool stuff quicker, not after you’ve worked around a bunch of default behavior that is sensible for a plain CMS but not so much for the kind of websites people have come to expect in 2010.

Documentation

Because of the added complexity of steering an existing system in the direction you want versus just building something, you’d expect that Drupal would be very well documented. Some parts of it are. The docs for the basic API‘s are pretty good. But those docs only work if you know full well what you want and what you’re doing.

Drupal lacks documentation on how all of its API‘s fit together, which is what makes the learning curve so tough on developers new to Drupal. And, as you’d expect, the documentation for user-contributed modules (which do most of the work for you) is mostly non-existent.

Contrast that with Django, which has a simpler architecture to begin with — it’s a framework, not a CMS — and has really good documentation on top of that. Django’s documentation is made up of step-by-step tutorials, topical guides and low-level reference material (cf. what Jacob Kaplan-Moss has to say about that) so people new to Django can get up to speed quickly, and gradually delve deeper without facing a wall.

Good documentation is probably the biggest contributor to programmer happiness. If the docs are good, you spend more time coding and less time scouring the web. Good docs feel empowering. Bad docs aren’t just frustrating, they also make you feel like an idiot.

Drupal made me feel like an idiot, Django doesn’t. I’m happy to have made the switch.

Stay tuned for a (shorter) second part about coder happiness in Drupal and Django, which looks at the issue from a bigger perspective: how running a project in both systems feels like.

share on twitter

Coder happiness in Drupal and Django, part I: hacking away debrouwere.org/11 by @stdbrouw

Stijn Debrouwere writes about statistics, computer code and the future of journalism. Used to work at the Guardian, Fusion and the Tow Center for Digital Journalism, now a data scientist for hire. Stijn is @stdbrouw on Twitter.