Tagging is a success story. Ten years ago, who would’ve thought that any regular Joe could and would be associating metadata with content. Out of their own free will, at that! Collections that would’ve just stayed a random pile of content in the past, like the bookmarks on Delicious or the photos on Flickr, are now being organized by the magic of folksonomies — a showcase for the sheer power of the many.

Tags dovetail nicely with our almost random way of browsing the internet, for instance by being the engine behind great topical pages for blogs that provide a gateway to any and all similar content written in the past. It’s metadata for the masses.

And so the human species does what we’ve always done when we see something that we like and that seems to work: we copy it. We’ve now got labels in GMail and in our customer relationship management software, tags in iPhoto, hashtags in twitter and there is tagging going on just about anywhere else where we want some order in what would otherwise be a big blob of undifferentiated content. And the world is better for it.

But because we’ve copied, thinking that if it’s good enough for Flickr, it ought to work for us too, we’ve forgotten what makes tags great, how they can add value and why they work when they work. We’ve forgotten that tags are just one way of bringing order to chaos.

Order to chaos

In the news industry, we desperately need to bring order to chaos. Amy Gahran says that today’s journalists should move away from their exclusive focus on content production ‘toward providing layers of journalistic insight and context’. A piece of news just doesn’t generate enough value on its day of birth to be worth the expense. Yet a day after publication, most content disappears in the depths of our websites, only to be found when a reader explicitly searches for it, if even then.

Each story could function as part of a web of knowledge around a certain topic, but it doesn’t.

So here’s a well-intentioned idea you’ve heard before: journalists should start tagging. Jay Rosen insists that Getting disciplined and strategic about tagging “may be one way professional journalism separates itself from the flood of cheap content online.” Tags can show how a news article relates to broader themes and topics. Just the ticket.

But too often, tags don’t live up to their promise. A techie at The Onion mentions that a while after they started tagging stories at their satirical news website, they had ended up with 20 or so different versions of “Bush Administration”, “George Bush”, “George W. Bush”, “Bush”, “bush” and so on, leading him to conclude that tags are evil:

The whole purpose of tags is to relate one piece of content to another, and if the relationship surface is spread out in such a way that we have 10 pieces of content tagged “bush administration” and 10 tagged “george bush” and the groups are orthogonal, even though they’re obviously related by tag name, the data indicates that they are completely different, and the goal of relating things is dead and someone has to go and look at all 10000 tags and decide which ones are thematically the same and remove the duplicates.

Getting strategic about contextualizing our content and bundling it into meaningful dossiers is definitely the future, Rosen is right about that. But such a strategy requires a way of indicating how content relates to other content on our website and on other websites that is more powerful and more expressive than tags. And let’s add another requirement to that challenge: we need this new way of relating content to other content to be easy to use and comprehend even for people who are not trained librarians. Simplicity is the sole reason tags work (when they work) so we can’t lose that.

But we do need something new. Tags are not the right way of disclosing the rich interconnections between news articles and not the right way of packing them together. Getting strategic about tagging means abandoning tagging and searching for something better.

Tagging on Flickr and Delicious works because the masses make it work by their aggregated behavior. Tagging on your personal blog works because you only want to bunch content together that is somewhat related and don’t really care about fancy-schmancy “relationships” between your content. Your readers don’t, either. They just want to read some similar stuff. But it’s different for news organizations.

We can do better

Let’s fix this.

What should we demand from a good categorization scheme?

- It should allow us to really talk about our content. One thing that upsets me about tags is that you can’t provide any more information above ‘this has something to do with that, but I can’t tell you what exactly the relationship is and neither can I tell you what the thing is that it relates to’.

- It should be easy to tag our content consistently. I hate careless tagging on news websites. If you’re not doing it right, don’t bother doing it at all. Me and my fellow readers are better off just using a search engine to find what we’re looking for.

As an addendum to (2): it should be obvious what we should tag and how we should tag it. Tagging is confusing for me, because half of the time I don’t know when something qualifies to be a tag or how I should tag. Is it relevant enough? Do we tag locations or just people and themes? Singular or plural form? Ehhhh. Here are the steps we can take to make things better.We need a scheme that combines some of the lessons we can learn from information architects with the simplicity of tags.

Step 1: vocabularies

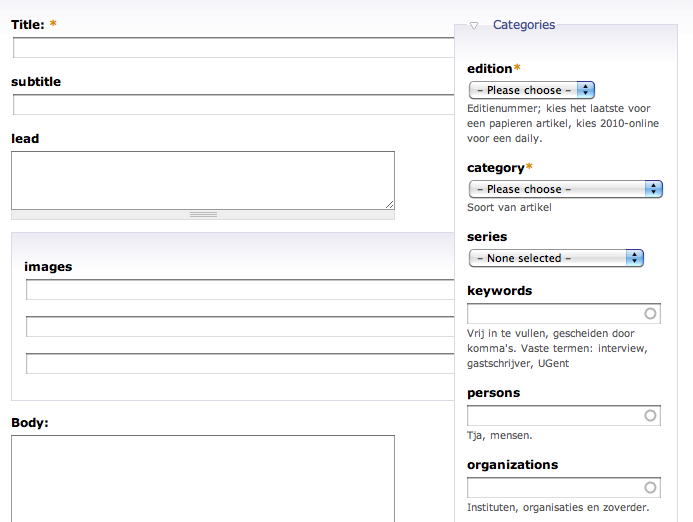

There’s a very simple step we can take to make it obvious to reporters what kind of things they are supposed to be adding as keywords to their articles. Split up tags by type, each with their own input field. Some people call ‘em vocabularies, others call them dictionaries, but you get the picture.

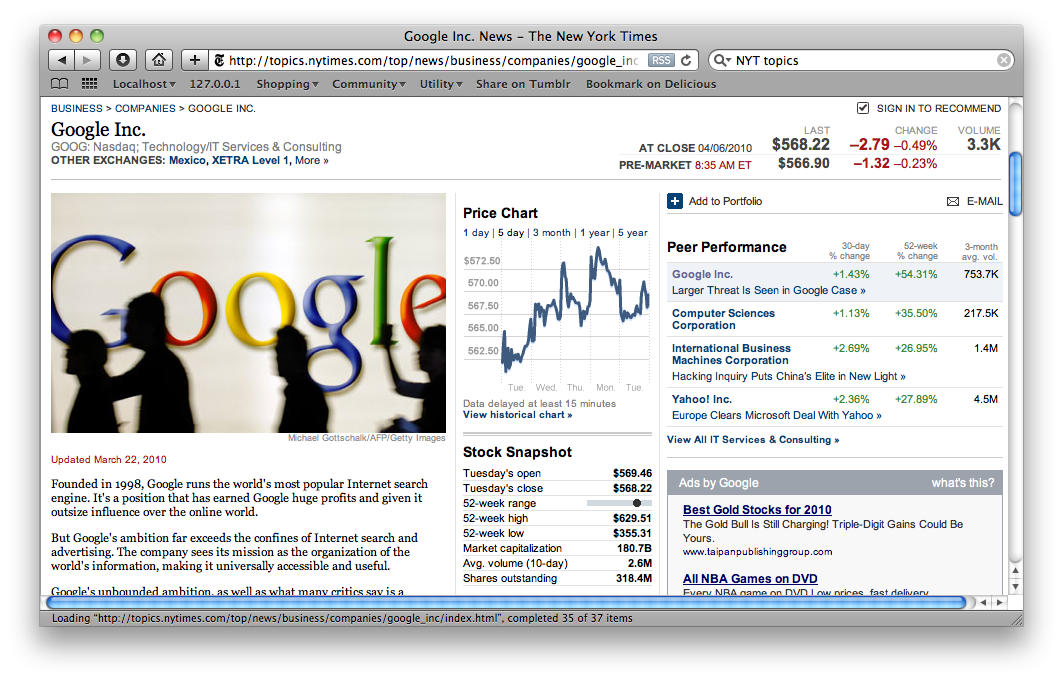

The New York Times has dictionaries for subject descriptors, persons, geographic locations and organizations. That’s pretty encompassing, but allow me to add events to that list.

Themes or topics, persons, locations, organizations, events. If we keep these five vocabularies in mind, they’ll serve as a constant reminder that we need to make sure that we keyword all the persons that are involved, that locations are valid keywords and that we should add them, and so on.

Vocabularies are a basic necessity for even trivial things like automatically compiling an index of all the people that a site has content on. You can’t provide an index of people if your website makes cannot discern persons from themes from locations.

We’ll handle subject descriptors — themes, topics, or whatever you want to call them — in a follow-up post scheduled for later this week. Themes often tie in with site navigation, which is tricky. Themes also come with their own knotty problems because, unlike persons or events, they’re not thing ish, they’re bundles. Don’t worry, themes and topics will get their own treatment in a day or two. Let’s first tackle the other vocabularies.

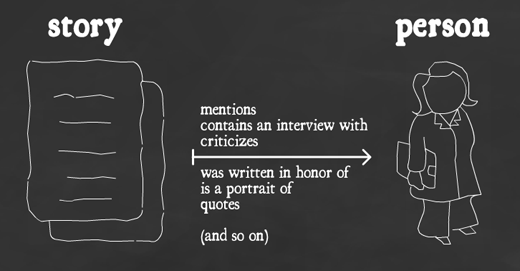

Step 2: abolish tags, state relationships

Tags are vague. They’re a very primitive way of spelling out how things relate to each other. A tag on a news article says “this article has something to do with this concept or thing”. But what exactly? A tag doesn’t tell you whether an article is a critique of a person, an interview with a person or whether it just mentions that person in passing. A tag doesn’t even tell you if the reference to Samuel Adams is about the person or about the kind of beer (which is why we so desperately need vocabularies). A tag can’t tell the difference between an event that merely took place at the local café and an event that the aforementioned pub actually organized.

It’s only a little confusing to us humans because we can guess the meaning of the tags from the text that they accompany, but computers can’t. We’re really going to need computers to aid us in bringing context — say, for example, listing all the articles where Apple was lauded versus those where the company was criticized.

With just a little more effort, it’s easy to specify real relationships. Let’s not reinvent the wheel. We’ll use use the triplets our semantic web buddies are so fond of:

<article> critiques <organization>

<article> contains an interview with <person>

<article> revolves around <event>

<article> follows up on <previous article>

<opinion piece> is a riposte vis-a-vis <other opinion piece>

The semantic web movement focuses on making the web understandable for computers, but this kind of metadata is useful for human readers as well. If I’m just skimming through an article and can’t be bothered to read it in its entirety, these relationships provide a pithy summary of what an article is about.

For example, the relationships for Clay Shirky’s The Collapse of Complex Business Models could look something like:

<analysis> is about <business models> (subcategory of <business>)

<analysis> is about <society>

<analysis> contains an example using <AT&T>

<analysis> criticizes <Rupert Murdoch>

Mkay, pithy might be overstating things a bit, but it’s a lot more insightful than what you get using plain tags.

Relationships can also be used to make search queries more intelligent. Here’s an example. I do a search on Politico for Rush Limbaugh. But, you see, I don’t care about mentions of Rush Limbaugh, just give me the articles that cite or interview him. Impossible on any news site I know of, trivial to implement with the right relationship-based metadata.

Relationships can also enrich topical pages and assure that they are more than just link dumps that leave the reader figuring out how exactly the linked content relates to the topic at hand.

Step 3: entities, not labels

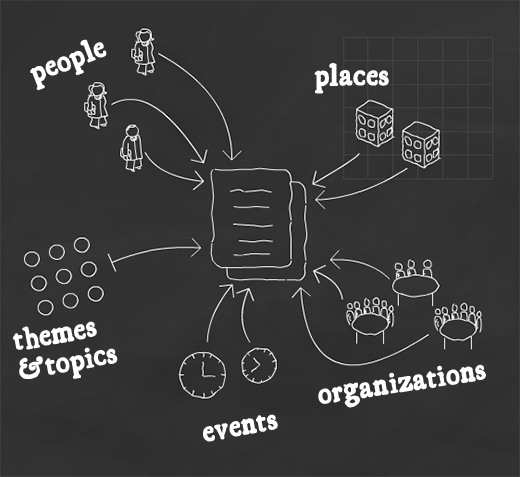

If we look at our vocabularies and ignore the topics/themes vocabulary for now, you’ll notice that these divisions actually represent real things. Persons. Organizations. Events. Locations.

Persons have first and last names, a birth date, they work for or are otherwise associated with certain organizations. People live somewhere.

Events happen at a certain place and at a certain time. They begin and they end. They might just be a point in time, or they can be planned happenings organized by a person, a group of persons or an organization. Events can recur weekly or monthly or yearly or randomly. Events can lead to other events.

A location has an address or at least refers to a geographical point or area.

Persons

- have a first and last name

- can belong to certain organizations

- can be implicated in certain events

- have a date of birth

- may have a personal homepage or blog

Organizations

- are active in a certain industry, market or sphere

- have members

- can collaborate with other organizations

- may have a physical presence in one or more locations

Events

- have a start date and an end date

- can recur at fixed or random intervals

- may be organized by persons or organizations

- can lead to or cause other events

- occur at a certain place, unless they’re virtual

Places

- can be a specific point in space or an area

- can often be pinpointed with an address

- can have a name (or a bunch of names)

Themes

- can contain subthemes or be part of larger themes

- can overlap with other themes

- can be used to situate stories, events, persons and organizations

Here’s a cool idea: let’s actually treat persons and events and all these other vocabularies like real things instead of like labels. Tags are a concept that we’ve inherited from the physical world: a tag is a label that you attach to something. And as David Weinberger notes:

in the physical world a label has to be smaller than the thing that it labels. That’s why we call it _meta_data: data about data.

But we don’t need the arbitrary distinction between a label and the thing it labels on a website. Let’s unlock the full potential of our relationships by making them relationships between things.

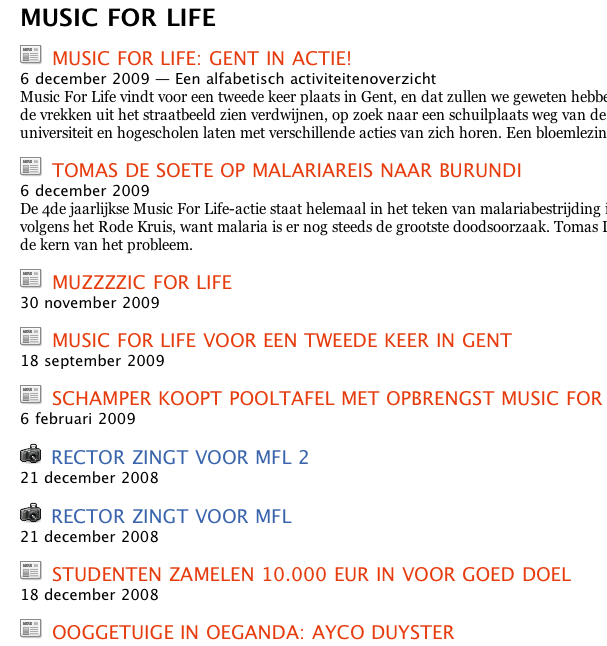

That way, the tag page for an event can show a map of where it took place. You could automatically place recent events you’ve covered on a calender. The tag page for a person can contain a biography, a timeline of significant events that this person was involved in and that you’ve reported about and so much more. And all this information can be gathered without human intervention, based solely on previously entered relationships, which gives you a good bit of automation without sacrifing quality.

Tag pages are fine as far as they go, but we have the ability to transform those rudimentary link dumps into valuable landing pages and content hubs that collect all the content for a person, an organization or an event. Pages that tie together a whole bunch of information on your website. Those topical pages can become a nexus and an alternative way of exploring what your site has to offer.

Lastly, when we’re thinking about entities, let’s not forget that news articles are a type of entity as well. We should be able to specify relationships to topics, be able to say that an article belongs to a series, and that an articles follows up on (or has another relationship to) a previous story.

Step 4: relationship cascades

One of our requirements for a tagging system was that it should be easy to be consistent and that it should make sure that we don’t forget to make the necessary connections. Relationship-augmented content can help with that. The trick: relationship cascades.

A person usually has meaningful connections to other people, places, events and organizations. When a tag is no longer just a tag, it can tell an entire story.

Barack Obama belongs to the Democratic Party and he’s from Chicago. If we tag an article with Barack Obama, it’s likely that the article also has something to do with the Democratic Party. If we’ve specified that the article is about Obama, and we’ve specified that Obama is part of the DP, the system now has all the necessary information to suggest our article about Obama as a possibly interesting related read on the topical page for the democratic party, even if we didn’t explicitly indicate that link.

How best to exploit those cascades? I see two ways.

- Automatic suggestions for readers: okay, but not great because they lack a human hand.

- Automatic suggestions for editors, serving as a basis for the entry of relationships.

If you tag an article with Barack Obama like we did above, a CMS can autosuggest a relationship to the Democratic Party, leaving it up to you to decide whether to add that relationship, but nonetheless providing a very clear suggestion.

We can also present these suggestions directly to the reader. I’m not a big fan of anything that reeks of autotagging (we’ll talk more about that below), but a case might be made for it. The quality of our relationships might drop if we trust in the relevancy of cascades too much (not every article about Obama has something to do with Chicago, on the contrary). On the other hand the system becomes more forgiving of forgetfulness, improving its coverage and breadth.

By smartly cascading down relationship chains, using the relationships that you have specified, additional relationships can be suggested to readers. It would probably take some experimentation to get these cascading relationships just right, but they’re worth a look.h3. Step 5: finishing touches — synonyms and homonyms

If we’re serious about creating a web of relationships on our website, we’d do well to follow a few best practices familiar to MLIS grads. Reqs that are boring but necessary. Like synonyms. We need a way to specify that NYU is equivalent to New York University.

Synonyms can be a help to editors because they don’t need to know the preferred term for an organization or location that’s already in the system. Editors should be able to enter any common name that describes the thing they’re thinking about, period. The system should be able to point a relationship to New York City, regardless of whether an editor just entered “Big Apple”, “NYC“ or “New York City”.

Readers demand the same leniency that synonyms bring: they don’t and shouldn’t care about the ideosyncracies in how you name things when they’re trying to find something. If somebody searches for Jon Stewart , they should be able to find the topical page for our beloved The Daily Show anchor just as easily than they would with the search query Jonathan Stuart Leibowitz.

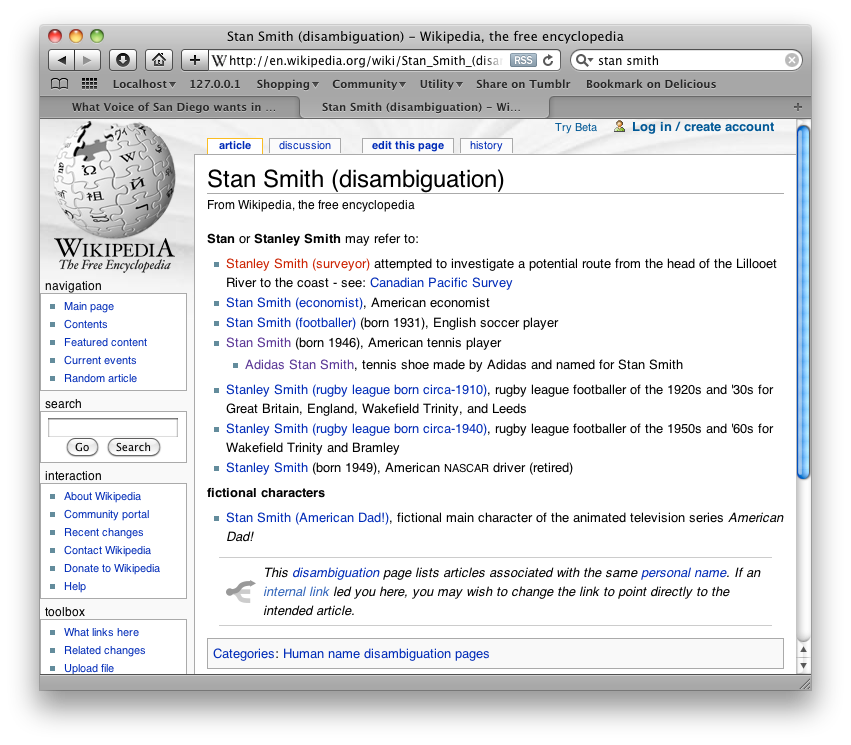

Names that can mean more than one thing should point to wikipedia-style disambiguation pages (but, in contrast to wikipedia, these pages should be autogenerated, not manually constructed). And the system should be able to differentiate between Stanley Smith the soccer player, Stanley Smith the tennis player and Stanley Smith the eponymous shoe by Adidas. (Should be able to, not must. A database of shoes would probably add little value to the vast majority of journalistic endeavors.)

In the really real world

Now what? I’ve presented a way of specifying rich relationships between articles and what these articles talk about. Relationships as I see them address the four important problems that tags have when used in a journalistic context. They provide a rich way of talking about your content. It’s metadata that says more than just “this has something to do with that”. Because you’re specifying relationships to things, it’s easier to remember what to link to and how to name those entities. And we can also specify relationships between articles, providing a better way of indicating previous reporting about a subject than the automated guesses we know as “related content” on most news websites.

That’s great. But I’m a firm believer in the mantra that ideas are useless — it’s the implementation and the nitty-gritty details that count. So we’re not done yet. We need to make sure that this way of tagging content (if you can still call it that) really kicks ass. In practice, not just in theory. Here’s the battle plan.

Step 1: make it easy

The first question that comes up in any entrepreneur’s mind when he sees the potential of contextualizing news and also sees the huge existing archives of content that are little more than plain text, is: can’t we automate this? After all, many of the relationships that we’d like to add to an article are ready to harvest from the text.

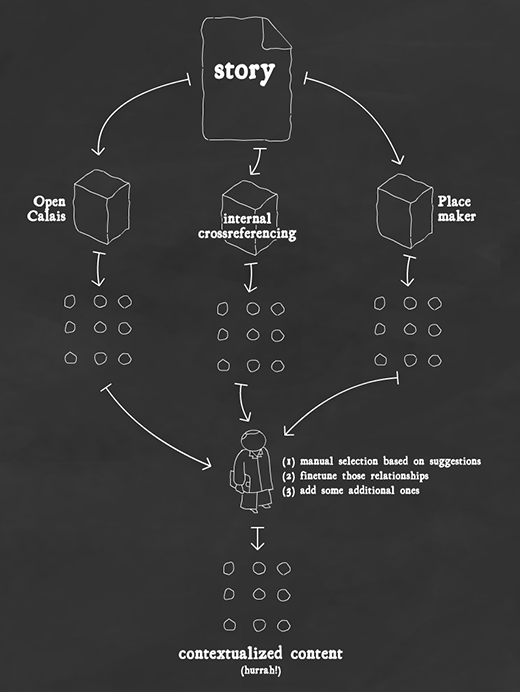

I mentioned autosuggestions/autotagging earlier. Names of persons can be spotted by cross-referencing body copy with Freebase and, if you’ve been entering relationships and entities for a while, with your own database of people. Same goes for organizations. Locations can be extracted using natural language analysis, e.g. using Yahoo! Placemaker. And we can add in links to other parts of the web using Apture, or even let Thomson Reuters’ Open Calais take care of some of our tagging needs.

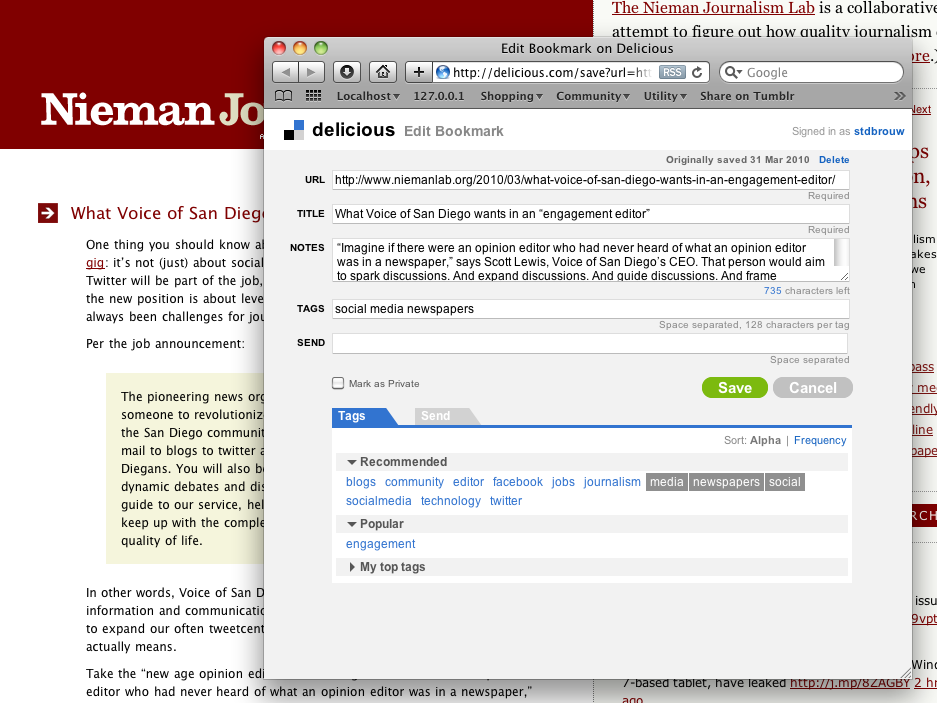

We should to take a very pragmatic approach to these tools. If you’ve tried them, you’ve seen that automated discovery tools like Open Calais just aren’t all that good. They will get better, but they’re not magical and they can’t see inside a journalist’s head. But what these automatic scans of your content do very well is give suggestions for relationships. As a reporter or an editor, you can then choose to flesh these out, use them as-is or ignore them. A bit like how suggestions work on Delicious, as shown above.

Those tools usually suggest related tags, or entities in our case. But we also have the relationships themselves to think about (a is an overview of x, b is a review of y, c contains an interview with z). To be useful, they have to be consistent too. We can’t bundle together all the articles where the mayor of San Antonio is asked for his opinion if one reporter enters that data as this article interviews the mayor, another as this article contains a few soundbites from the mayor and yet another one codifies it as this article quotes the mayor.

We’d best stick to a few agreed-upon relationships for the majority of the cases. We should provide the means of adding new predicates, but gently guide reporters to a basic set of relationships.

If we really do need the detailed relationships above (e.g. the difference between ‘interviews’ and ‘contains soundbites’), it’s not impossible. We’d just need a way of specifying which relationships are roughly equivalent. And the right mechanisms in place to make sure that every once in a while editors comb through relationships and tidy them up a bit.

As with curating plain ol’ tags, you’ll have to weigh whether the added detail justifies the added work.

Step 2: make it maintainable

Which brings us to the second crucial issue we need to address if a relationships-based web of content is to be successfully implemented. It has to be maintainable.

Any good implementation of relationships in a CMS should be able to merge different terms or entities. It should give a birds-eye view and suggest possibly problematic content, using symptoms such as too few relationships or a lot of autosuggested relationships that are not being used. We can make it as painless as possible, but structuring your content as a web of relationships isn’t and can never be maintenance-free. This is just as true for plain tags, as they found out over at The Onion.

Although relationships present a bit more work on the part of the journalist or editor entering the content, maintaining the consistency and quality of the relationships should actually be easier than with plain free tags like the ones you see in Wordpress and just about any other CMS out there.

A lament that I’ve often heard from journalists is that it’s hard to know what they should enter in a tag field. Keywords can be anything. What makes a keyword a keyword? What if a keyword would be relevant but really not at all central to the content of the article? Relationships to real entities give a natural answer to these questions.

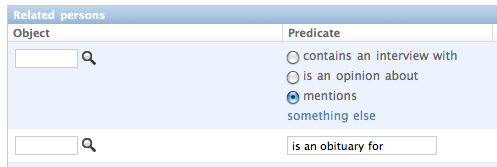

It’s pretty evident that you’ll want to add references to persons where it says “add related persons to this article”.

Tags are vague as to how the content should relate to the tag, and to the importance that that relationship entails. Relationships aren’t. You can enter a relationship from an article to an organization which specifies that an article discusses momentous events for but just as well that an article just mentions in passing or mentions as an example a certain company. The question “is this important enough to tag” doesn’t arise. One less thing to worry about.

Real relationships make explicit what tags implicitly suggest. Because relationships are so explicit, they’re easy to grasp and easy to enter correctly and comprehensively.

Step 3: make it worthwhile now

Introducing tagging into a newsroom, whether the traditional free tags or the relationship-infused ones I’m proposing, is a cultural issue. The challenge is getting authors and editors to see tagging as an enrichment of their content, rather than a nuisance that is being forced upon them from above.

If you’re the big chief at your organization, you could make it a policy that journalists should tag their content if they expect to get paid. But if their heart isn’t in it, journalists won’t do it consistently and the value of your web of relationships drops.

The utility of tagging is most apparent in the long term, with hundreds or thousands of interrelated articles, but we need some enticement now to bridge that gap and sweeten the deal.

Luckily, relationships to real entities can be the foundation for a lot of added value in the here and now.

Because a location isn’t just a tag, but has an actual geographical area associated with it, a good content management system can easily make a map of all the locations that are mentioned in an article or in a series. I write the code that puts locations on a map once, and from that point on, adding a map to an article becomes as simple as clicking ‘gimme a map!’ in my backend.

Specifying a relationship to a person means a little inline biography visible alongside the article is only a click away.

Events can easily be bundled into elegantly styled timelines.

Taking things one step further, if you provide topical pages for locations, persons and organizations like the NYT does , a healthy dose of vanity will entice journalists to relate their articles to the right topics, persons and organizations. It’s the only way they can get their work on those topic pages. Being such an easy way for journalists to increase the shelf life of their work, you’d think they’ll make the effort.

Beat reporters will need even less encouragement to make use of relationships. Relationships can serve as an internal tool to keep track of a beat. Reporters can keep an overview of their field and share that knowledge with fellow reporters. We’re not there yet, but hopefully we can someday get to the point where a content management system stops being a mere tool to publish to the web, and becomes a digital notebook that aids journalists in their work.

In summation

Tags are labels without any context. Tags are vague, and it’s difficult to tag content consistently.

We need to re-engineer tags so that they’ll allow us to represent the rich relationships between our content and the things that content talks about. If we do that, newspapers can infuse the news with necessary context that allows readers to see the broader picture. Quite literally, too: relationship-infused content can easily be enriched with maps and timelines, which goes way beyond what tags have to offer.

Tags have a deceiving simplicity that hides their complexity as a taxonomic concept. Relationships are closer to the way journalists think about their writing. Relationships are a direct answer to the question “what is this story about?” Because they’re more intuitive than tags, they’re actually harder to mess up.

If we re-imagine tags as rich connections that relate content to the persons, organizations, locations, events and themes they talk about, hopefully magic will happen.

share on twitter

Tags don't cut it debrouwere.org/1a by @stdbrouw

Stijn Debrouwere writes about statistics, computer code and the future of journalism. Used to work at the Guardian, Fusion and the Tow Center for Digital Journalism, now a data scientist for hire. Stijn is @stdbrouw on Twitter.