Wednesday I suggested that we could solve a lot of problems with tagging if we start thinking in terms of relationships to real things instead of seeing tags als mere labels. With tags as true entities it’s easy to figure out what to tag (you tag persons, organizations, locations, events) and how to tag it. Relationships can be a part of the foundation for the kind of contextualized journalism that we hope to see more of in the future.

However, while talking about the future of metadata, I carefully sidestepped a thorny issue. Tags aren’t always used to refer to persons or locations. Even more often, tags are used to categorize content by a broader theme or by subject. Themes or topics aren’t real things, they’re bundles of things. Bundles of things upset the carefully crafted scheme I set out earlier. Today I’ll talk about polyhierarchy as a way of getting topics and themes into the fold.

Taming topics

One requirement of a good categorization scheme in particular is a bit more difficult to fulfill for topics than it is for, say, organizations or locations. Namely that it should be easy to tag our content consistently. If you’re specifying a relationship to John Smith, it’s beyond obvious that you want the relationship to point to that person. But if you’ve just written an article about strife in Bosnia, how would you tag that? Bosnian muslims, religious strife, geopolitical conflicts, war, conflict, politics? Or maybe all of the above?

How broad or how narrow should a bundle be? How would we indicate that one bundle (religious strife) belongs to another bundle (conflicts)? Do we want to indicate that at all, or is it okay to just tag your article with both religious strife and conflict and be done with it?

First the bad news. There are a couple of ways to tame thematic categorization, but maintaining metadata is never going to be a walk in the park. You can’t avoid periodic gardening of your categories. Every once in a while, you’ll want to check the consistency, quality and completeness of your efforts. Removing pointless themes and topics, merging some topics together and splitting others. We’ll also need some guidelines in place that determine how and what we should tag. Deciding which themes properly describe a story isn’t always straightforward or obvious.

Turning a disadvantage into an advantage

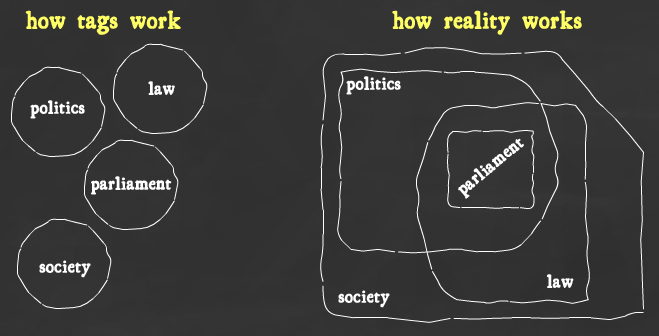

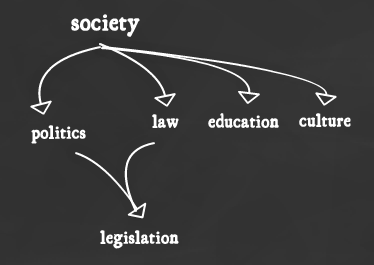

There are a few partial solutions, though. Topics and themes are bundles and bundles are hard to get right, IA-wise. But topics and themes also have two interesting properties that we can exploit for some information architecture magic. One: topics can overlap. Two: topics can contain other, more specific topics.

Because topics serve to cluster news stories together in sets, we can’t just represent them as a flat structure, which tags would force us to do. Articles abouthigher educationare a subset of the articles abouteducation, to give but one example. Topics are better represented by a tree structure.

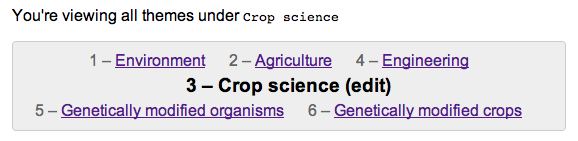

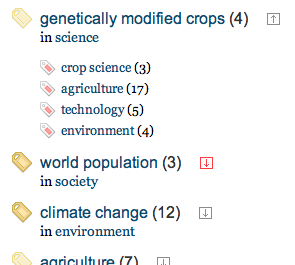

Tree structures make it really easy to be comprehensive in your tagging efforts. Provided you have well-cared for tag hierarchies in place, tagging a piece of content with the themegenetically modified cropswill, by association, also mean that it will be tagged with its parent categoriescrop science,engineering,agriculture,environmentand so on.

I like schemes that are forgiving of forgetfulness. Hierarchies are forgiving if anything is: associated tags can very often make up for oversights in tagging. It just doesn’t matter if an editor writing a piece on Monsanto forgets to tag his article withenvironment, because he’s probably tagged it withgenetically modified organisms,agricultureor one of a host of other related tags, which all haveenvironmentas a parent term.

Curation is for computers

Whereas regular tags leave one wondering if a tag might be too specific to really be useful, hierarchies can help by taking the decision out of our hands. Be as specific as you like. A little algorithm can easily count if a certain tag has surpassed a critical treshold (it links together, say, at least five stories) and if it hasn’t, display the parent tag to your readers instead. Filtering on the way out is easier than filtering on the way in.

You can keep little-used tags in the system without ever bothering users with them, and without having to decide beforehand if these tags will become useful or not. If ever you do decide to remove the tag because it’s just too specific to act as a good bundle, the fact that it is part of a hierarchy makes it easy to merge associated content into the parent category.

Ordering topics in hierarchies might not look as easy as the appealing tag-based flatland, but they open up new possibilities you don’t want to miss out on. True enough, hierarchies are not as simple as flat tags and you’ll need to invest a bit more time in them, but they also take an otherwise decision out of your hands and out of your mind. They also allow you to stop worrying so much about whether you’ve tagged your content comprehensively.

Polyhierarchy

But placing topics in a tree brings its own challenge. To which supercategory does the topic “Christian schools” belong — education or religion? Luckily it’s a problem that is easily solved. Just allow a topic to have more than one parent category. That’s not possible in the physical world where every item has to be in one bucket and one bucket only, but it’s perfectly possible in the digital world. Information architects call it polyhierarchy, mathematicians and computer scientists call it directed acyclic graphs.

In practice

I see you wondering how one would ever create a UI that makes it easy to

- reference existing tags

- add new tags to the hierarchy

- specify multiple parent tags

- change or add new parents

Keeping in mind that most journalists still aren’t as web-savvy as we would like, any feasible interface for polyhierarchic tags is liable to cause brain melt, I’d have to agree. Which is why we’d better split up the process in two phases: entry and curation.

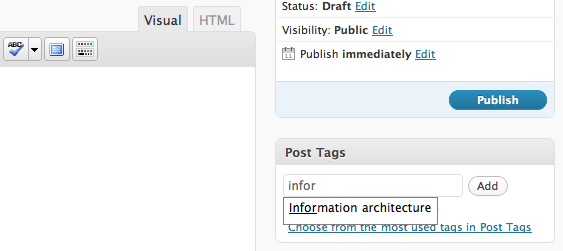

We can keep the familiar tagging interface we know from Wordpress, Drupal and similar systems: an input field with comma-separated tags and an autocomplete widget that suggests existing tags. It keeps the learning curve low, since most people are familiar with this type of interface.

Part two is a bit more involved. Editors get an interface that consists of two buckets: one with tags that are already part of the hierarchy, and one with tags that were recently added and as such aren’t part of the hierarchy yet.

Such an interface should make it easy to get a good birds-eye overview of the tag hierarchy. Editors can then click through to a tag, which exposes a form in which you can specify the parent tags that make a topic part of the larger hierarchy.

Newly added tags stay invisible for readers, until we’ve had the chance to make them part of the hierarchy. (Remember: tags are only useful if they bundle together a reasonable number of articles; newly added tags never do.)

And that’s that.

Polyhierarchical tags solve two important problems. One tag implies a bunch of related and synonymous tags, so adding tags no longer means racking your brain trying to be complete when summing up related themes for a story. And you can stop wondering whether the tags you’re entering are too specific or too vague. Just enter the most specific tags you can think of, and let the hierarchy take care of displaying more general tags if necessary. Adding hierarchy to your tags is an investment, but one that pays off.

share on twitter

Themes and topics debrouwere.org/1b by @stdbrouw

Stijn Debrouwere writes about statistics, computer code and the future of journalism. Used to work at the Guardian, Fusion and the Tow Center for Digital Journalism, now a data scientist for hire. Stijn is @stdbrouw on Twitter.