It’s now three and a half years ago that Adrian Holovaty told developers that we needed to start thinking about how we structure news website content as a prequisite to the new and exciting things everybody wants The New Journalism to do.

We’ve seen some exciting developments in the journalistic landscape. Lots of talk about new business models and mumbling about mashups and clouds and multimedia. But nobody really seems to have taken Adrian’s advice to heart. So it shouldn’t surprise us that most news websites still look more or less like a print product that has been transplanted to the web.

Some of the startups that get everyone excited like The Huffington Post, Talking Points Memo or The Voice of San Diego do provide excellent content, and they do provide something that wasn’t there before, but as much as as they’re rethinking the newsroom, they’re not reinventing the news website.

Rethink the basics

There’s a lot of excitement about infographics nowadays, and I love those myself. People get all warm and fuzzy about news apps and I do too. But ultimately, when thinking about the future of journalism on the web, they’re distractions. Infographics and news apps feel like the best thing since sliced bread, because they allow us to do revolutionary new stuff, without rethinking any of the basics of online news production. Experimenting with infographics is low-risk and low-cost, so why wouldn’t you?

But we’re forgetting the most important point at issue: what should a news website look like in 2010 and beyond? The fundamentals of website design and information architecture somehow lack appeal as a topic for debate among journos. To make things worse, it’s difficult or impossible to talk management into a strategic rethink of all your web assets. So even though we know damn well that we need to think on a deeper level about how online news should work, we push those nagging doubts to the back of our brains, and commission another cool infographic that will surely make the rounds on Twitter, or a news app that’ll be used all over the web as an example of the bright future of journalism.

Let’s not kid ourselves. A new way of doing journalism requires new technology to support and foster that innovation. That technology should reach right into the core of our journalistic endeavors, not just touch the periphery like yet another infographic or mashup.

Why would we want structure?

According to Adrian Holovaty, newspapers should be in the information business, and think further than the written word. Structured information is what will fuel innovation in journalism. I couldn’t agree more.

The biggest problem in explaining why we should abandon big blobs of text, in favor of structuring our content, is that it isn’t always clear in what way we’ll get a return on investment. As Holovaty notes, it’s often about serendipity.

One day in the future, a journalist might walk in and ask “Wouldn’t it be really cool if we could create a map of all our restaurant reviews and allow people to filter by the kind of food they offer and by price?” — if you’ve been storing evaluation, price range and cuisine separately from the text of the review, that’s something a coder can hack together in a day, but if the text is all you have, forget about it.

Serendipity isn’t the word we’re looking for, though, because it’s not about happy coincidences like the above, but about purposely creating the technological environment that provides the magic to make almost any “wouldn’t it be cool if we could…”-style reverie a reality.

There are tangible, direct benefits to be had as well.

Lack of structure hampers design, structure makes design easy. If corrections and updates to an article are part of the body text, you can’t decide later on whether you want them displayed above the article or below it or to the side, unless you feel up to a few days or weeks worth of copy-pasting infoboxes around.

Don’t even think about providing a track my errors feature like Slate (‘This hand-built RSS feed will ring every time Slate runs a “Press Box” correction.’) unless you want to actually hand-build it.

If you codify the questions of an interview simply as bolded text, you’ll only ever be able to display them as bolded text, regardless of what your designers would wish for.

Structured content also leads to effortless repurposing. Displaying content in a way that’s tailored to each specific platform — mobile, e-reader, mail, print, web — is just a matter of taking the structure that’s there, and designing the experience any way you want. When I worked at the local student newspaper during my college days, getting content into InDesign to layout our biweekly newsmag was a simple matter of just importing a little XML file, straight from our website. That’s how easy repurposing can be if you make the effort to decouple information from presentation.

How did we end up here?

Something we who grew up with the web tend to forget, is that newspapers have been thinking about how to structure their digital newsrooms and their content since the dawn of affordable personal computers. Most so-called enterprise solutions for newsrooms are still desktop applications that may allow quick publishing to the web, but aren’t of the web.

The first tangible efforts at structuring news were ANPA 1312 by the Newspaper Association of America in the late seventies and IPTC 7901 by the International Press Telecommunications Council in the early eighties. The world wide web didn’t exist, and these standardized formats mainly served to push content from news agencies to newspapers in a predictable way, and to support easy exchange of syndicated content among news organizations. Both ANPA 1312 and IPTC 7901 are still in use right now for exactly those use-cases. Just to give an idea, the specs for the latest edition of IPTC 7901 include:

- a source identification: “To provide a means to identify the news service of the originator and the message.”

- message priority: “To indicate the editorial urgency of a story.”

- a category: “To denote the category of a story.”

- a keyword: “To index the story contained in the message”

In the nineties, the NITF format (at first based on SGML, later based on its simpler descendant, XML) added, among other things:

- who owns the copyright to the item, who may republish it, and who it’s about.

- what subjects, organizations, and events it covers.

- when it was reported, issued, and revised.

- where it was written, where the action took place, and where it may be released.

- why it is newsworthy, based on the editor’s analysis of the metadata.

It’s kind of humbling to see that even a quarter of a century ago, news formatted in International Press Telecommunications Council standards like IPTC 7901 , NITF or NewsML had more metadata associated with it than a lot of websites of today.

The “big blob of text” phenomenon we’re stuck with now wasn’t caused by newspapers sticking to their old, wary ways, but by the transition to a new medium, the internet. Web publishing tools, even those that exist today, more often than not don’t lend themselves to the structured entry of content.

Still, the structured metadata offered by formats like NITF isn’t all sunshine and roses. Traditional approaches to structured news content are seriously hampered by their focus on standardization and exchange. NITF is incredibly useful, but exchange between different news orgs and import/export between different software platforms is really all it is useful for. No wonder that news executives don’t see the advantage of structuring their content online — we don’t exchange our web content with any partners, so why bother with fancy-schmancy XML-based formats?

In 2006, Adrian Holovaty put the issue back on the table, at the same time refocussing the discussion: nowadays it’s not about standards or interoperability, it’s about bringing out the structure in your specific content in a way that serves your goals. That kind of structure will be different for each newspaper because they all have different formats and different beats.

From here to there

Narrative is a crucial part of good journalism, but it’s not enough, not anymore. The news industry needs to start thinking about journalism in terms of information and the myriad ways in which we can present that information to our readers. Daniel Jacobson, director of application development over at NPR , sums it up as follows: build a content management system, not a web publishing tool.

The goal of any CMS should be to gather enough information to present the content on any platform, in any presentation, at any time. WPT’s capture content with the primary purpose of publishing web pages. (Daniel Jacobson)

But it’s not just about being display-agnostic, it’s about being agnostic about use as well. The first day a story is published, the narrative will undoubtedly be the most important aspect of the coverage, but later on a story can get a second life in a database, become part of a mashup or be displayed as an entry on a topic page. And for those purposes, we don’t care about narrative, we crave information.

How to get started, though? Daniel’s advice to “gather enough information” is rather vague as a guideline. Here’s what you do: model the problem domain.

Model the problem domain

Software engineers solve problems in numerous different industries and for organizations from all parts of society. Each of those niches has its own way of talking about things and faces its own problems. Software architects learned early on that writing software isn’t just about writing algorithms and routines, it’s about grasping the problems somebody is facing, and helping them solve those problems. Unraveling those problems can only be done by thinking about what engineers call the problem domain, and by abstracting that domain into a domain model. Let’s borrow that terminology.

The goal is to make our content management system like a miniature world in a snowglobe. Not just a system that publishes text, but a system that talks like we do: it knows that an interview implies one or more interviewees, it understands that a story can have multiple authors and that those authors can be guest authors without an account on the website. It knows that stories can be related to previous stories.

A domain model is a representation of your newsroom and the world that you cover. With a domain model, journalists have an easier time understanding how everything in the system hangs together, and programmers have an easier time working on the site.

Part of the problem domain comes from the beats you cover and the style of reporting you do, another part comes from the way journalism works: articles are related to authors and perhaps to an edition of a print product. They’re often related to certain persons, events or themes. So part of the domain model can be thought out as a communal effort and serve as a resource for any and all newspapers, but beyond that, it’s up to you.

How does structured news actually look like? Allow me to repeat Holovaty’s examples of the latent structure in many stories (they’re that great):

- An obituary is about a person, involves dates and funeral homes.

- A wedding announcement is about a couple, with a wedding date, engagement date, bride hometown, groom hometown and various other happy, flowery pieces of information.

- A birth has parents, a child (or children) and a date.

- A college graduate has a home state, a home town, a degree, a major and graduation year.

- An Onion-style On the Street feature has respondents, answers and a publication date.

- A drink special has a day of the week and is offered at a bar.

- The schedule of the U.S. Congress has a day and multiple agenda items.

- A political advertisement has a candidate, a state, a political party, multiple issues, characters, cues, music and more.

- Every Senate, House and Governor race in the U.S. has location, analysis, demographic information, previous election results, campaign-finance information and more.

- Every known detainee at Guantanamo Bay has an approximate age, birthplace, formal charges and more.

At first, obituaries, “on the street” features and reporting about election races would seem like any other story, providing few opportunities to apply some order. But take the time to really figure out what kinds of content you produce. Think about the basic elements of reporting that lie hidden behind the narrative readers get to see. You’ll soon get the hang of it.

A domain model consists of two parts: entities and relationships between those entities. Both entities and relationships can have certain properties.

- A membership is a type of relationship that has a start and an end date.

- A review has a title, a lead, a score and so on, as well as a relationship to the book, movie or whatever is being reviewed.

Some entities also have associated actions as well: perhaps users can rate a review, members have accounts that can be activated or deactivated, stories can be shared on Facebook.

Here’s a quick checklist to make sure you’ve really got the domain model down, and haven’t lumped too many different entities together.

- Are there certain properties of a broad entity (like “story”) that you only use for a very specific genre of reporting? An interview has an interviewer and one or more interviewees, whereas a news item has neither. Might want to split those off into two different entities.

- Each story consists of a narrative and a bunch of assets or resources: photographs, infoboxes, rating cards. What are yours? These are entities too.

- Do your entities have any plain text properties that are actually more than just plain text? Specifying a license on a photograph by adding it to the caption isn’t wise; the photo should refer to a license entity instead.

Another example. I’ve seen quite a few print publications that catalogue their stories online under an issue number. But is a story part of the issue number? Not really, it’s part of an issue. And an issue is more than just a number: it has a date of publication, a cover image, a chief editor, it might revolve around a special theme, it has a circulation, it has one or more cover stories. Don’t think too soon that something is just a number or merely a line of text.

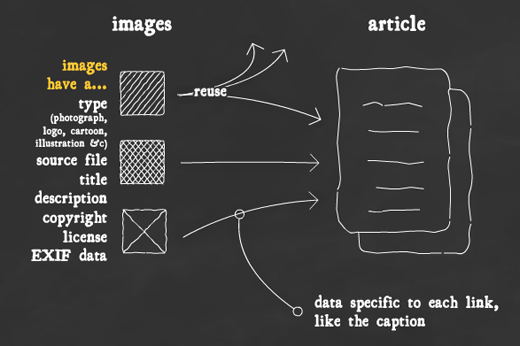

Similarly, an illustration or photograph might look like just another part of a text, but it’s more than that: in addition to the source file (the image itself), every photograph has an author, a copyright holder and perhaps a license, might contain one or more persons and was taken at a location. You can probably think of a few additional ones yourself.

Markup means something’s wrong

It’s unavoidable. The most important part of a story is still the written copy. However, the fact that the body consists of nothing more than strings of text doesn’t mean that there is no structure to be found. We emphasize parts of our text by putting it in italics, we indicate the questions in an interview by putting them in bold, we give subtitles a bigger font. Emphasis, questions and subtitles are structured text if anything is.

The problem isn’t that body text doesn’t contain any structure, the problem is that we can’t get it out. That’s because we commonly codify that structure using presentation: we make text bigger, we put it in italics, we give it another color. But computers can’t translate from presentation to structure. And often, our presentation is not entirely consistent from one story to the next either. So presentation has to go.

Presentation is a designer’s job, and it doesn’t concern journalists or editors. It shouldn’t be a part of content entry. How you want to mark things up for display might change. It probably will. But what something is won’t change. So avoid markup, and think structure instead.

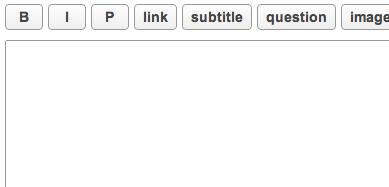

We should be able to generate HTML or any other markup on the fly, based on how a text is structured. That means we need domain-specific ways of indicating, err, marking up a text. We need to start creating our own little Markdown-like languages for journalism.

What is structure, anyway?

Holovaty’s example are great, but they’re also fairly narrow. Almost every example is a case of splitting up a piece of content into its constituent parts, and storing that structured information alongside the story. Defining properties on entities can be an immensely powerful tool, but it is not the only way there is to apply structure and metadata. The nature of a piece of content is often determined more by how it relates to other content and other entities than by its properties. That’s why I started this series with a post on tagging and relationships. In a way relationships between entities are more fundamental than the domain entities themselves.

Well thought-out entities with the right properties work best with fixed formats — standardized ways of reporting about a certain subject. If a piece of content doesn’t satisfy that criterium, don’t bother. It’s no use trying to push content that’s only semi-structured into a mold it hardly fits. Going light on structured entities and heavy on relationships often works better in that case.

For example it might make more sense to indicate that something is an interview by defining relationships to the persons being interviewed (<article> contains an interview with <person>) rather than specifying a separate interview content type with an interviewee or interviewees property. After all, many reports and news stories contain interviews as well, even though you wouldn’t classify them as an interview if asked the genre. Relationships allow for some flexiblity in that regard.

Pragmatic looseness

Thinking in terms of entities and relationships is one of those things, like mathematics, that feels entirely foreign the first time you see it, something you think you’ll never grasp, but once you finally get it, you really do get it. Humans are predisposed to see patterns and structure where there is none. Don’t get carried away.

Jonathan Stray recently expressed the worry that too much structure and strict relationships between content can squeeze the life out of things. And it’s true, be careful. Apply too little structure and your website becomes an unmaintainable mess; haphazardly apply structure and you’ll never get a return on investment.

Try to really get a feel for the complexity of the endeavor. Realize that relationships aren’t necessarily objective or neutral:

Is Taiwan a country? Is a tomato a vegetable? Where’s the line between terrorist and freedom fighter? Do we really care about the subtle distinctions between Syrah, Merlot and Pinot Noir? Aren’t they all just red wines? It depends who you ask. Very few domains are exempt from this complexity (Peter Morville, Ambient Findability, p. 134)

Entities can present a challenge as well. Take authorship. Most content management systems get this entirely wrong. Most of them don’t support multiple authors. They don’t differentiate between authors and editors. They don’t handle guest authors and if you need pseudonyms to accompany a piece of satire, you’re out of luck. Indicating who wrote what looks trivial but it isn’t.

Thinking in terms of relationships and entities pays for itself many times over, but don’t underestimate the challenge in doing it right.

How do we get there?

We’ve seen how entities and relationships can help us fashion a news website that’s ready for the future. We know there are some pitfalls to be avoided. Now, how do we build this stuff?

As Daniel Jacobson rightfully mentions, most software labeled “content management system” is actually a web publishing tool in disguise. And a lot of people complain about their content management systems for exactly that reason.

- Scott Klein says those in the news industry should think again if they suppose that any old CMS can serve as a development platform that will support the innovation in the media we so desperately crave.

- Clay Johnson of the Sunlight Foundation says “See— the problem with a full scale Content Management System is that it has too many opinions. Those opinions were though[t] of by somebody other than you and the needs of your organization. The more developed a content management system (or any piece of software, really) the more “opinions” it has. And the more “opinions” it has, the more likely one of them is going to really tick you off.”

- Adrian Rossouw, who develops in Drupal, one of the most flexible CMSes out there, complains that even with Drupal a lot of time is “spent undoing the assumptions that Drupal has baked into core directly”.

I really don’t want to talk anybody into using any specific product or service. That’s not the point of this series, and it would only serve to piss people off for ridiculing their choice of software. However, I don’t want to leave readers clueless either when it comes to actually experimenting with and implementing some of my advice and suggestions. You can’t just hack together the type of information architecture that I champion on any old Wordpress installation, unless you’re feeling particularly masochistic.

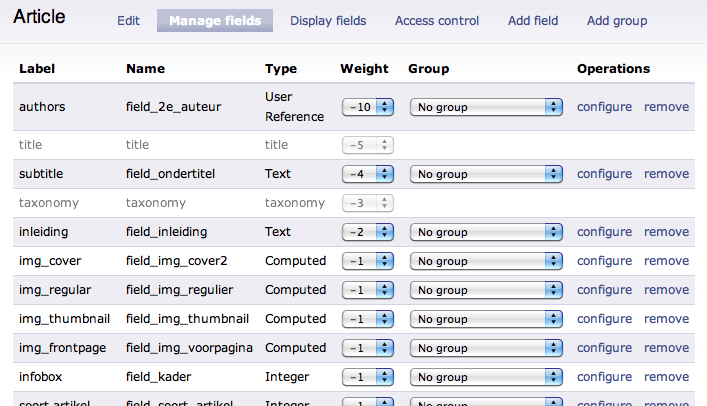

So if most CMSes are actually WPTs, rendering them unusable in our endeavors, how do we proceed? One way of approaching the problem that I particularly like is to take a step back, and build your website using a web framework instead of an off-the-shelf content management system. A web framework is like a toolkit for building your very own content management system. It provides a lot of basic building blocks every site needs so you don’t have to reinvent the wheel, but everything else is up to you. Ruby on Rails is probably the most well-known framework out there. Django is another one. It has proven especially popular with computer programmers working for newsrooms.

In Django, development begins by defining the data models that describe the organization, publication, or site. For example, these might be Stories, Authors, and Presses, or Equipment, Schedules, and Reservations, or Faculty, Students, Courses and Evaluations, etc. All of these have datatypes and interdependent relationships. […] Starting with the data modeling process is a key point. Django makes no assumptions about the needs of your organization or the shape of your data, which means the end product should fit your organization like a glove. (Scot Hacker)

Put more generally:

The proposal of Django is “organize your thoughts conceptually, and I will present them” – as opposed to “put your documents in my system and I will display them” (which seems to me what the CMS approach is). (Rob Nelson)

Frameworks seem particularly suited to the challenges the news industry is facing right now. We need experimentation now more than ever, we need the freedom to build a website that matches our vision, we need to do things that have never been done before. That’s not what Wordpress was made for#.

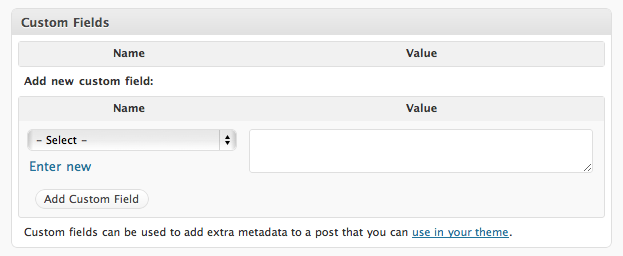

If you’re not using a framework or don’t want to, don’t let that stop you from structuring your content, though. Wordpress and similar blogging platforms can get you some of the way using custom fields. Drupal additionally makes it fairly doable to specify relationships between your content. It might not be exactly what you want, but a little structure can go a long way.

Peace of mind is like a piece of heaven

As the web evolves, people will come to be ever more demanding in their news consumption. Just a few days ago, Robert Pickard was complaining about how most media companies are still trying to sell nineteenth and twentieth century products in the twenty-first century. We’re perennially playing catch-up, and we’re failing. Newspapers can try to save their online reputation with one-offs — a news app that maps local crime, some data viz for election day, the occasional liveblog — but it won’t matter.

Innovation should be aimed at the heart of what we do. Innovation should allow us to do exciting things with everyday news. Innovation should be all-encompassing. Making the news more engaging should be easy, it should flow naturally from our content management system. Our technical infrastructure should reward reporters and coder/journalists with unexpected low-hanging fruit, instead of forcing us to jump higher and higher whenever we want to go the extra mile for our readers.

Building a content management system tailored to the specifics of your newsroom and the readers you serve isn’t about building castles in the sky. It isn’t about “building an infrastructure because it can be done” as Bart Anderson worries. It’s about laying the foundation for the future of journalism and cutting costs while doing so.

A well-architected news website requires that we move beyond thinking of a website as just a means of publishing stories. The published stories and their presentation is but the tip of the iceberg. The future of news will require content management systems that are savvy not just to the realities of the newsroom, but to the specifics of your content and to the workings of your community, your beats, your strategic goals.

A well-architected news website leads to content that will keep on providing value, rather than leaving stories to wither away when their immediate news value has faded. Structured content is the stuff that makes a website malleable, rather than cementing you into certain ways of doing things. Structured content is like a big undo button that allows you to reverse decisions and change how your website looks and behaves. Since none of us can predict the future, the freedom to change course as often as we please and not having to worry about escalating legacy costs, well, that’s pretty close to heaven.

share on twitter

We're in the information business debrouwere.org/1f by @stdbrouw

Stijn Debrouwere writes about statistics, computer code and the future of journalism. Used to work at the Guardian, Fusion and the Tow Center for Digital Journalism, now a data scientist for hire. Stijn is @stdbrouw on Twitter.